What is Natural Capital?

John Lockhart of Nicholsons and Kate Russell of Tellus Natural Capital Ltd explain what natural capital is and what opportunities it can offer to landowners.

Why is Natural Capital Important?

Despite the fact that natural capital is now common currency in the language of environmental policy and strategy, there is still a huge amount of confusion around what it really is and what relevance it has for people’s lives and businesses.

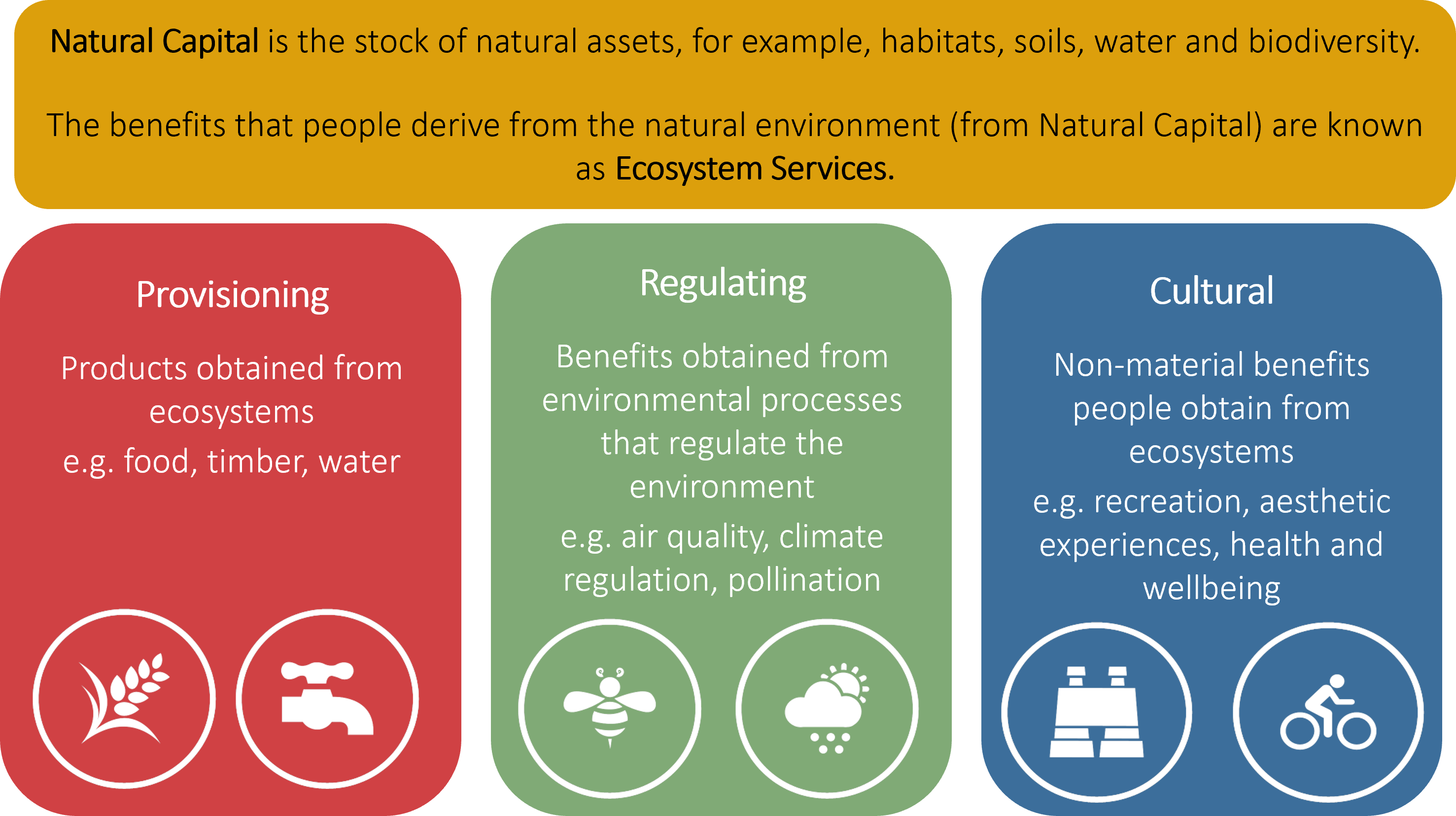

So, what is natural capital? Quite simply, it’s our stock of fresh and marine waters, soils and minerals, air, flora and fauna: the assets provided by nature that have the capacity to generate goods and services. Ultimately, it is the source of all other types of capital, whether manufactured, financial, human or social.

“The elements of nature that directly and indirectly produce value or benefits to people, including ecosystems, species, fresh-water, land, minerals, the air and oceans, as well as natural processes and functions.” Natural Capital Committee (2014)

The benefits that natural capital yields are known as ecosystem services – a rather dry technical term for the huge range of benefits that we get from nature, food and timber to air filtration and recreation.

Traditional private markets recognised and paid for the provisioning services so that land managers were incentivised to deliver them, but the huge range of other ecosystem services were undervalued and often ignored by society, delivered only as “freeriders”. To change this, we first need to identify and recognise all these additional benefits and then find ways to value them.

Why does this matter? The short answer is that the degradation of our natural capital is an important issue for everyone, both personally and professionally. If, as a society, we keep drawing down on our natural capital without reinvesting, it will eventually no longer be able to support us.

Does Government policy support natural capital?

For over fifteen years the government has affirmed its commitment to the environment through legislation, policy papers and target setting, from the Natural Choice White Paper of 2011 stating the wish to be “the first generation to leave the natural environment of England in a better state than it inherited…” to the Dasgupta Review on the Economics of Biodiversity published in 2021.

The statutory and regulatory frameworks, including the Climate Change Act 2008 which enshrines the Net Zero by 2050 commitment, the 25 Year Environment Plan, the Agriculture Act 2020 and the Environment Act 2021 are all in place. Recent wobbles by Rishi Sunak on the implementation dates for some environmental policies aside, the path ahead is clear at a local, national and global level: we can and must do more to tackle nature depletion and climate change.

Where do we start?

On the basis that you can’t value what you can’t see, we need to start by learning to identify and map our natural capital. This requires a change in perspective from the traditional land management approach: where once we might have mapped farmland, woodland and “amenity” areas, we now look to identify the core natural capital assets which can deliver those valuable ecosystem services. That means we want to understand and map the soil type, slope and aspect, existing habitats, waterbodies and the situation of the land in relation to rights of way, infrastructure, settlements and natural features. From this information we can start to construct a natural capital asset register.

The next step is to identify the benefits that flow from those assets. These might include water quality regulation delivered by riparian vegetation as it captures sediment and run-off from adjacent land; carbon sequestration by woodland, permanent grassland and saltmarsh; contribution to health and wellbeing from public access across rights of way; or air filtration benefits of hedges and trees planted along road verges which absorb particulates from vehicle exhausts. The particular benefits which arise will depend on the situation and wider context of the land as well as its physical nature: the ability of a hedge to mitigate flood risk by slowing run-off will depend on where it is in relation to the watercourse as well as the slope and the nature of the vegetation around it, for example.

The final and perhaps most challenging step is to ascribe a value to those ecosystem services. In some cases there is market evidence, such as from sales of carbon credits under the Woodland Carbon Code or sales of nutrient credits for pollution reduction, but in other cases we have to rely on tools designed by environmental economists to find a societal value, including by reference to:

- Costs saved – e.g. savings to the water company of reduced treatment costs where sediment and nutrients have been removed by riparian woodland

- Willingness to pay – based on surveys to ascertain what people would be willing to pay to visit a scenic location

- Hedonic pricing – used to explain differences in property values due to proximity to green open space, for example.

These valuation approaches enable us to build up a different type of assessment of the natural capital value of land: where once we might have looked at a woodland and seen timber value, sporting value and perhaps amenity value, we would now identify a much longer list of valuable services.

Since 2019 the government has published a set of Natural Capital Accounts for the UK in an attempt to identify the financial and societal value of our natural resources; the 2022 accounts, which looked at data from 2020, estimated the total asset value of the UK’s natural capital to be £1.8 trillion. Within that assessment, the annual value of air quality regulation services was estimated at £2.4 billion and that for the health benefits of recreation in nature at £6.8 billion. The values for natural capital are now being revealed to be very significant.

But are these values real?

One of the key challenges is the current lack of simple pathways to market. There is now so much solid evidence of the benefits that the natural environment delivers to society, but the mechanisms to provide realistic levels of financial support to the landowners and managers who provide these benefits are still in their infancy. Progress is being made, however, and these are the natural capital markets which we are starting to see:

- Nutrient neutrality – in affected catchments, property developers are now required by regulation to make their developments “nutrient neutral”. One way to do so is to pay for long term land use change, which will reduce the levels of nitrates or phosphates upstream of the development.

- Biodiversity Net Gain – new laws come into effect from January 2024 in England which will mean that any development requiring planning consent will be obliged to deliver 10% Biodiversity Net Gain. There are opportunities for landowners to create habitat banks to sell Biodiversity Units to developers.

- Carbon credits – the Woodland Carbon Code and Peatland Code are the standards governing carbon sequestration schemes and enabling landowners to sell verified carbon credits for use as offsets. This is a voluntary market and current demand for credits is somewhat sluggish at the moment.

- Natural flood management – there is increasing policy interest in this issue as understanding grows of the ways in which water flows can be slowed down and stored on land to reduce downstream flood risk. Some projects are demonstrating that “buyers” can be found to pay landowners for long term land use changes, but there is some way to go before this becomes a real market. Defra has recently announced £25 million of funding for more pilot projects.

- Green social prescribing – the health benefits of access to nature are better recognised since the Covid-19 pandemic and NHS England has recently completed a two-year study into the concept. Expect to see more of this, particularly in areas close to towns and cities, where people can more easily access green space.

- Air quality filtration – the values ascribed to air quality regulation services are very considerable, but we have yet to see a mechanism emerge to convert them into income streams for land managers. It may come in future as another cost of development, like BNG, or as an aspect of Green Social Prescribing.

Is there a role for public funding?

In England we are now halfway through the agricultural transition plan: the Sustainable Farming Incentive is being rolled out, some payment rates under Countryside Stewardship have been increased and we are promised a new, improved “Countryside Stewardship Plus” scheme in 2024. These schemes offer the benefits of certainty and predictable income streams, making them an attractive option to many farmers, but they can also be used to start establishing baseline data for future projects.

The next step up in public funding is Landscape Recovery and the second-round bids are currently being assessed. Landscape Recovery will fund a landscape-scale project through two years of development, after which it is expected to have found some private funding to secure long term land use change. This “blended finance” option of public and private funding is seen by many as the most likely long-term solution to the problem of funding environmental restoration and long-term management.

Final thoughts

As landowners, managers and stakeholders we need to get onto the front foot. In the first instance, we need to identify, map and value our natural capital assets, considering how they fit within the wider network of green infrastructure. We then need to consider who needs what we have and ensure that we work together with both private sector and public sector partners to develop lucrative market opportunities.

Enhancing natural capital makes good practical economic sense; the challenge now is to develop programmes and structures that start to properly reward landowners for the real value that the provision of these public goods provides to society as a whole.